The U.S. Army named the Bell UH-1 helicopter "Iroquois" from a standing tradition of naming Army helicopters after Native American names. The name "Huey" derived from the designation of UH-1, stuck and "Iroquois" did not. Thus the name "Huey". Ralph's "Huey" was a troop carrier and resupply "ship". Ralph referred to it as a "ship" in his letters home. It was also called a "slick" because it had slick sides with no external armament. But it did have machine guns at the cabin doors. Ralph's unit came under The First Cavalry (Airmobile) Division. "Airmobile" meaning that troops could be carried into battle by helicopter. The Huey was the work horse of the Vietnam War. And the sound of the blades in motion is synonymous with the Vietnam War. It was an endearing sound to ground troopers!

Glenn Hess shared a compliment he was given by a Chief of Police several years ago. "The Chief of Police had been a Marine grunt. When he found out that I was an Army helicopter pilot he told me that whenever they were in contact and had wounded they prayed that it would be an Army Huey that was sent because they knew Army guys would get them out. No greater compliment."

The following is a blog post written by COL Keith Nightingale on 21 May 2016. COL Nightingale kindly gave permission to post here.

THE SOUND THAT BINDS

Unique to all that served in Vietnam is the UH1H helicopter. It was both devil and angel and it served as both extremely well. Whether a LRRP, US or RVN soldier or civilian, whether, NVA, VC, Allied or civilian, it provided a sound and sense that lives with us all today. It is the one sound that immediately clears the clouds of time and freshens the forgotten images within our mind. It will be the sound track of our last moments on earth. It was a simple machine-a single engine, a single blade and four man crew-yet like the Model T, it transformed us all and performed tasks the engineers and designers never imagined. For soldiers, it was the worst and best of friends but it was the one binding material in a tapestry of a war of many pieces.

The smell was always hot, filled with diesel fumes, sharp drafts accentuated by gritty sand, laterite and anxious vibrations. It always held the spell of the unknown and the anxiety of learning what was next and what might be. It was an unavoidable magnet for the heavily laden soldier who donkey-trotted to its squat shaking shape through the haze and blast of dirt, stepped on the OD skid, turned and dropped his ruck on the cool aluminum deck. Reaching inside with his rifle or machine gun, a soldier would grasp a floor ring with a finger as an extra precaution of physics for those moments when the now airborne bird would break into a sharp turn revealing all ground or all sky to the helpless riders all very mindful of the impeding weight on their backs. The relentless weight of the ruck combined with the stress of varying motion caused fingers and floor rings to bind almost as one. Constant was the vibration, smell of hydraulic fluid, flashes of visionary images and the occasional burst of a ground-fed odor-rotting fish, dank swampy heat, cordite or simply the continuous sinuous currents of Vietnam’s weather-cold and driven mist in the Northern monsoon or the wall of heated humidity in the southern dry season. Blotting it out and shading the effect was the constant sound of the single rotating blade as it ate a piece of the air, struggling to overcome the momentary physics of the weather.

To divert anxiety, a soldier/piece of freight, might reflect on his home away from home. The door gunners were usually calm which was emotionally helpful. Each gun had a C ration fruit can at the ammo box clip entrance to the feed mechanism of the machine gun. The gun had a large circular aiming sight unlike the ground pounder version. That had the advantage of being able to fix on targets from the air considerably further than normal ground acquisition. Pears, Apricots, Apple Sauce or Fruit Cocktail, it all worked. Fruit cans had just the right width to smoothly feed the belt into the gun which was always a good thing. Some gunners carried a large oil can much like old locomotive engineers to squeeze on the barrel to keep it cool. Usually this was accompanied by a large OD towel or a khaki wound pack bandage to allow a rubdown without a burned hand. Under the gunners seat was usually a small dairy-box filled with extra ammo boxes, smoke grenades, water, flare pistol, C rats and a couple of well-worn paperbacks. The gun itself might be attached to the roof of the helicopter with a bungi cord and harness. This allowed the adventurous gunners to unattach the gun from the pintle and fire it manually while standing on the skid with only the thinnest of connectivity to the bird. These were people you wanted near you-particularly on extractions.

The pilots were more mysterious. You only saw parts of them as they labored behind the armored seats. An arm, a helmeted head and the occasional fingered hand as it moved across the dials and switches on the ceiling above. The armored side panels covered their outside legs-an advantage the passenger did not enjoy. Sometimes, a face, shielded behind helmeted sunshades, would turn around to impart a question with a glance or display a sense of anxiety with large white-circled eyes-this was not a welcoming look as the sounds of external issues fought to override the sounds of mechanics in flight. Yet, as a whole, the pilots got you there, took you back and kept you maintained. You never remembered names, if at all you knew them, but you always remembered the ride and the sound.

Behind each pilot seat usually ran a stretch of wire or silk attaching belt. It would have arrayed a variety of handy items for immediate use. Smoke grenades were the bulk of the attachment inventory-most colors and a couple of white phosphorous if a dramatic marking was needed. Sometimes, trip flares or hand grenades would be included depending on the location and mission. Hand grenades were a rare exception as even pilots knew they exploded-not always where intended. It was just a short arm motion for a door gunner to pluck an inventory item off the string, pull the pin and pitch it which was the point of the arrangement. You didn’t want to be in a helicopter when such an act occurred as that usually meant there was an issue. Soldiers don’t like issues that involve them. It usually means a long day or a very short one-neither of which is a good thing.

The bird lifts off in a slow, struggling and shaking manner. Dust clouds obscure any view a soldier may have. Quickly, with a few subtle swings, the bird is above the dust and a cool encompassing wind blows through. Sweat is quickly dried, eyes clear and a thousand feet of altitude show the world below. Colors are muted but objects clear. The rows of wooden hootches, the airfield, local villages, an old B52 strike, the mottled trail left by a Ranchhand spray mission and the open reflective water of a river or lake are crisp in sight. The initial anxiety of the flight or mission recede as the constantly moving and soothing motion picture and soundtrack unfolds. In time, one is aware of the mass of UH1H’s coalescing in a line in front of and behind you. Other strings of birds may be left or right of you-all surging toward some small speck in the front lost to your view. Each is a mirror image of the other-two to three laden soldiers sitting on the edge looking at you and your accompanying passengers all going to the same place with the same sense of anxiety and uncertainty but borne on a similar steed and sound.

In time, one senses the birds coalescing as they approach the objective. Perhaps a furtive glance or sweeping arc of flight reveals the landing zone. Smoke erupts in columns-initially visible as blue grey against the sky. The location is clearly discernible as a trembling spot surrounded by a vast green carpet of flat jungle or a sharp point of a jutting ridge, As the bird gets closer, a soldier can now see the small FAC aircraft working well-below, the sudden sweeping curve of the bombing runs and the small puffs as artillery impacts. A sense of immense loneliness can begin to obscure one’s mind as the world’s greatest theatre raises its curtain. Even closer now, with anxious eyes and short breath, a soldier can make out his destination. The smoke is now the dirty grey black of munitions with only the slightest hint of orange upon ignition. No Hollywood effect is at work. Here, the physics of explosions are clearly evident as pressure and mass over light.

The pilot turns around to give a thumbs up or simply ignores his load as he struggles to maintain position with multiple birds dropping power through smoke swirls, uplifting newly created debris, sparks and flaming ash. The soldiers instinctively grasp their weapons tighter, look furtively between the upcoming ground and the pilot and mentally strain to find some anchor point for the next few seconds of life. If this is the first lift in, the door gunners will be firing rapidly in sweeping motions of the gun but this will be largely unknown and unfelt to the soldiers. They will now be focused on the quickly approaching ground and the point where they might safely exit. Getting out is now very important. Suddenly, the gunners may rapidly point to the ground and shout “GO” or there may just be the jolt of the skids hitting the ground and the soldiers instinctively lurch out of the bird, slam into the ground and focus on the very small part of the world they now can see. The empty birds, under full power, squeeze massive amounts of air and debris down on the exited soldiers blinding them to the smallest view. Very quickly, there is a sudden shroud of silence as the birds retreat into the distance and the soldiers begin their recovery into a cohesive organization losing that sound.

On various occasions and weather dependent, the birds return. Some to provide necessary logistics, some command visits and some medevacs. On the rarest and best of occasions, they arrive to take you home. Always they have the same sweet sound which resonates with every soldier who ever heard it. It is the sound of life, hope for life and what may be. It is a sound that never will be forgotten. It is your and our sound.

Logistics is always a trial. Pilots don’t like it, field soldiers need it and weather is indiscriminate. Log flights also mean mail and a connection to home and where real people live and live real lives. Here is an aberrant aspect of life that only that sound can relieve. Often there is no landing zone or the area is so hot that a pilot’s sense of purpose may become blurred. Ground commander’s beg and plead on the radio for support that is met with equivocations or insoluble issues. Rations are stretched from four to six days, cigarettes become serious barter items and soldiers begin to turn inward. In some cases, perhaps only minutes after landing, fire fights break out. The machine guns begin their carnivorous song. Rifle ammunition and grenades are expended with gargantuan appetites. The air is filled with an all-encompassing sound that shuts each soldier into his own small world-shooting, loading, shooting, loading, shooting, loading until he has to quickly reach into the depth of his ruck, past the extra rations, past the extra rain poncho, past the spare paperback, to the eight M16 magazines forming the bottom of the load-never thought he would need them. A resupply is desperately needed. In some time, a sound is heard over the din of battle. A steady whomp whomp whomp that says; The World is here. Help is on the way. Hang in there. The soldier turns back to the business at hand with a renewed confidence. Wind parts the canopy and things begin to crash through the tree tops. Some cases have smoke grenades attached-these are the really important stuff-medical supplies, codes and maybe mail. The sound drifts off in the distance and things are better for the moment. The sound brings both a psychological and a material relief.

Wounds are hard to manage. The body is all soft flesh, integrated parts and an emotional burden for those that have to watch its deterioration. If the body is an engine, blood is the gasoline.-when it runs out, so does life. Its important the parts get quickly fixed and the blood is restored to a useful level. If not, the soldier becomes another piece of battlefield detritus. A field medic has the ability to stop external blood flow-less internal. He can replace blood with fluid but its not blood. He can treat for shock but he can’t always stop it. He is at the mercy of his ability and the nature of the wound. Bright red is surface bleeding he can manage but dark red, almost tar-colored, is deep, visceral and beyond his ability to manage. Dark is the essence of the casualties interior. He needs the help that only that sound can bring. If an LZ exists, its wonderful and easy. If not, difficult options remain. The bird weaves back and forth above the canopy as the pilot struggles to find the location of the casualty. He begins a steady hover as he lowers the litter on a cable. The gunner or helo medic looks down at the small figures below and tries to wiggle the litter and cable through the tall canopy to the small upreaching figures below. In time, the litter is filled and the cable retreats -the helo crew still carefully managing the cable as it wends skyward. The cable hits its anchor, the litter is pulled in and the pilot pulls pitch and quickly disappears-but the retreating sound is heard by all and the silent universal thought-There but for the Grace of God go I-and it will be to that sound.

Cutting a landing zone is a standard soldier task. Often, to hear the helicopter’s song, the impossible becomes a requirement and miracles abound. Sweat-filled eyes, blood blistered hands, energy-expended and with a breath of desperation and desire, soldiers attack a small space to carve out sufficient open air for the helicopter to land. Land to bring in what’s needed, take out what’s not and to remind them that someone out there cares. Perhaps some explosives are used-usually for the bigger trees but most often its soldiers and machetes or the side of an e-tool. Done under the pressure of an encroaching enemy, it’s a combination of high adrenalin rush and simple dumb luck-small bullet, big space. In time, an opening is made and the sky revealed. A sound encroaches before a vision. Eyes turn toward the newly created void and the bird appears. The blade tips seem so much larger than the newly-columned sky. Volumes of dirt, grass, leaves and twigs sweep upward and are then driven fiercely downward through the blades as the pilot struggles to do a completely vertical descent through the narrow column he has been provided. Below, the soldiers both cower and revel in the free-flowing air. The trash is blinding but the moving air feels so great. Somehow, the pilot lands in a space that seems smaller than his blade radius. In reverse, the sound builds and then recedes into the distance-always that sound. Bringing and taking away.

Extraction is an emotional highlight of any soldier’s journey. Regardless of the austerity and issues of the home base, for that moment, it is a highly desired location and the focus of thought. It will be provided by that familiar vehicle of sound. The Pickup Zone in the bush is relatively open or if on an established firebase or hilltop position, a marked fixed location. The soldiers awaiting extraction, close to the location undertake their assigned duties-security, formation alignment or LZ marking. Each is focused on the task at hand and tends to blot out other issues. As each soldier senses his moment of removal is about to arrive, his auditory sense becomes keen and his visceral instinct searches for that single sweet song that only one instrument can play. When registered, his eyes look up and he sees what his mind has imaged. He focuses on the sound and the sight and both become larger as they fill his body. He quickly steps unto the skid and up into the aluminum cocoon. Turning outward now, he grasps his weapon with one hand and with the other holds the cargo ring on the floor-as he did when he first arrived at this location. Reversing the flow of travel, he approaches what he temporarily calls home. Landing again in a swirl of dust, diesel and grinding sand, he offloads and trudges toward his assembly point. The sounds retreat in his ears but he knows he will hear them again. He always will.

This is the photo that accompanied COL Nightingale's blog post that Bob Witt had shared on facebook. Coincidently the downed helicopter in this photo is of a bird from C/227 (Ralph's unit).The backstory to the photo is provided by Duane Caswell (C/227) and Bob Witt (A/227). The photo they believe was taken on LZ Pepper days following the initial assault on the A Shau Valley on 19 April 1968. (Ralph also flew this mission and briefly wrote home about in a letter home on 4 May 68 that you can read further down the page). Duane believes that the helicopter in the photo was his (Yellow Three) that crashed soon after MAJ Burkhalter's Yellow One crashed and burned while attempting to land in the LZ. Duane had attempted to land up the hill from where MAJ Burkhalter had crashed to put out his troopers and pick up Yellow One's crew; but his bird crashed too. (No one was killed in either of these two crashes just banged up!) Duane says the LZ was not as big as the photo makes it look and the DA was higher than they thought. (DA - Ratio of moisture to temperature that tells you how much your rotors will lift.) Duane also commented that most of C/227 had to hitch a ride home that day and added "life is tough some days". Bob Witt adds that he flew in behind C/227 with A/227 who finally made it into the LZ after being shot up on approach and that he will never forget the C/227 crew member acting as a ground guide on that terrible slope.

Two additional photos courtesy of Duane Caswell (C/227)

Ralph participated in many missions while assigned to C Company, 227th Assault Helicopter Battalion (C227AHB). Some were operations that were named and others were not.

Ralph flew many hours and had become an Aircraft Commander by June or July.

~11 June 68 - "Pretty soon I'll be made an AC which is an Aircraft Commander. This means that I'll be the pilot and will be in charge of the ship. The person who flies with me will be the co-pilot. Lately I have been flying a lot of hours so they can make me an AC earlier. This past week I've been flying with a guy who has been here as long as me and we've been taking turns each day as AC."

This was probably Charles Callahan - known to his family as Larry and in country as Chuck.

Terry Pestel a fellow C227AHB pilot and friend told me that Ralph and Chuck flew a lot together.

YouTube Memorial to Charles Callahan

English Class Project

Westlake High School, Austin, TX

By Mary Travis - Junior

Rebecka Stucky - Teacher

Ralph writes about some of the first times "up" in Vietnam!

~27 Mar 68 - "I am pretty well settled at Camp Evans and today I went up for the first time with one of the experienced pilots. It was kind of an orientation ride to get me a bit familiar and also to work the rust out of my joints. This afternoon we went down to the marine base at Phu Bai to pick up some maps and some sandbags and we flew over Hue. Just from looking at it you could tell it was once a beautiful city. It's really a mess now."

~29 Mar 68 - "I flew yesterday on a Command and Control mission which just means that we flew a couple of colonels to another base about 15 miles away then we flew down to Phu Bai to pick up some supplies and bring mail back. ...Oh! When we were flying back from Phu Bai yesterday we flew low level up the rivers and part of the coast and buzzed some Navy River Patrol boats. We all got a kick out of that!"

~1 April 68 - "There's not much to say about flying because I have haven't been up in 4 days, we have a shortage of helicopters in my company. When I was talking to Bob (Witt) yesterday he told me he had 20 hours flying already, I've only got 8 hours. I'll be going up tomorrow I hope."

~3 April 68 - "I've got 20 hrs flying now and there's still a lot to learn about it over here. Its harder to fly over here than it was in school. We have to carry heavy loads such as 7 troops with full gear and its harder to land and harder to takeoff."

~7 April 68 - "I flew a couple of hours last night and today we flew down to Phu Bai to pick up a helicopter that had some repairs done to it and flew it back here."

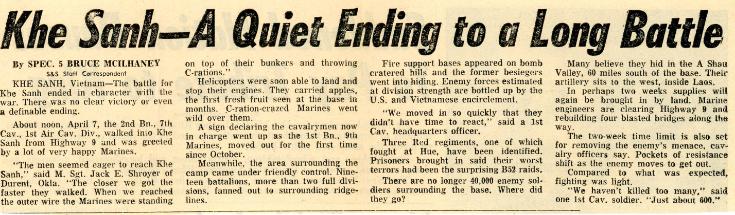

One of the first named missions that Ralph participated in was the relief of the Marines at Khe Sanh.

It was named Operation Pegasus.

~8 April 68 - "The 1st Cav has been having operations up there in the mountains. I've been up there twice and tonight I won't be sleeping here at Evans because we're going up to a small camp about 8 miles from Khe Sanh. The camp is in a valley and we generally base all our operations around Khe Sanh from there. The camp has a small airstrip and we'll be flying out of there for tomorrow. ...I didn't fly yesterday but the 1st Cav put 2000 Avn (South Vietnamese) troops into Khe Sanh.The operation going on up there is called Operation Pegasus because in ancient times Pegasus was a fabled flying horse. The patch of the 1st Cav is a shield shaped patch of yellow with a diagonal black stripe and a horses head in the corner. The operation is named after the Cav."

~9 April 68 - "Yesterday I flew 11:45 minutes. Some of us stayed over at a small camp northwest of here and the next day we flew supply missions all around Khe Sanh. Today we have to go up there again and stay over and probably do the same thing."

~13 April 68 - "The last few days have been real bad. It's been rainy + cool. I've got about 50 hrs. flying now and one day I flew 11 hours + 15 minutes. Yesterday I flew 9 and a half. I'm sending a clipping from one of the newspapers we get. I think it's from the stars and stripes. We've been flying up around Khe Sanh and a couple of times I almost flew over it. I could of had some good pictures if I had a camera."

~16 April 68 - "I've been flying quite a bit now and I'm starting to learn how these big operations and missions are run (it's complicated)."

~18 April 68 - "Today I flew from 7 o'clock to 6 o'clock and then I had to go out at 7PM and fly till 8:30. Well right now I'm pretty tired and I have to fly tomorrow so I'm going to get some sleep."

Photos of Operation Pegasus (Khe Sanh)

Courtesy of Charlie Company, 1st Battalion, 5th Calvary, 1st Calvary Division

Facebook page - Charlie Company, 1st Battalion, 5th Calvary, 1st Calvary Division Veterans

Both 227AHB and 229AHB participated in Operation Pegasus. Possible initial mass insertion into LZ Peanuts.

*It is possible that Ralph could of been flying one of these Huey Troop Carriers!

Photo courtesy of Bennie Koon - HHC,1st Battalion,5th Cavalry,1st Cavalry Division

*Check out the dog on the left hand side!

Both 227AHB and 229AHB participated in Operation Pegasus. Possible initial mass insertion into LZ Peanuts.

*It is possible that Ralph could of been flying one of these Huey Troop Carriers!

Photo courtesy of Bennie Koon - HHC,1st Battalion,5th Cavalry,1st Cavalry Division

Both 227AHB and 229AHB participated in Operation Pegasus. Possible initial mass insertion into LZ Peanuts.

*It is possible that Ralph could of been flying one of these Huey Troop Carriers!

Photo courtesy of Bennie Koon - HHC,1st Battalion,5th Cavalry,1st Cavalry Division

Both 227AHB and 229AHB participated in Operation Pegasus. Possible initial mass insertion into LZ Peanuts.

*It is possible that Ralph could of been flying one of these Huey Troop Carriers!

Photo courtesy of Bennie Koon - HHC,1st Battalion,5th Cavalry,1st Cavalry Division

Operation Delaware - Assault into the A Shau Valley

19 April 1968

The morning of 19 April 1968

Staging area prior to the assault into the A Shau Valley

Framed Photo Courtesy of Bill Peterson - C227AHB Crew Chief

This card was inspired by Bill Peterson's letters home while assigned to C227AHB.

Two cards came home with Ralph's belongings.

~26 April 68 - "That newspaper article you sent looked familiar. I've been all around Khe Sanh and took part in the Operation. We are all through up there now and now we are working in the A Shau Valley,"

~4 May 68 - "Oh By the way , All the pilots in my Company who flew the 19th of April for the 1st assault into the AShau Valley (which includes me) are up for the the D.F.C. (Distinguished Flying Cross) its the highest medal for flying, it'll take months for the paper work. ...P.S. It was a pretty bad day (the 19th). My flight was the first ones into the A Shau."

~6 May68 - "Last week I wasn't flying much but yesterday I flew 13 hours and today I flew 6 hours and I'm supposed to fly tomorrow too."

~11 May 68 - "...we moved all the troops out of the A Shau valley. The infantry mined the whole valley with plastic mines. (they can't be detected.) It will be a while before the NVA can use it again."

~12 May 68 - "I've got some pictures of the A Shau valley from one of the LZ's (landing zones) and I've also got some from the air that show some of the NVA bunkers and spider holes around the base of LZ tiger which was the first place we put troops when we invaded the A Shau. LZ Tiger was the very top of a 3,800 foot mountain. On the 1st day of the A Shau I was the third ship out of 40 to drop troops on Tiger. By tomorrow all the troops should be extracted from the Valley. I don't know if it was mentioned in the papers or not but the NVA had 3 airstrips in there called A Luoi, Ta Bat, A Shau. Our intelligence sources said one of them was being used at night from planes coming from Laos."

~16 May 68 - "The day before yesterday I flew down to Da Nang for a mission. That night we slept there and that was quite a change because we had beds with mattresses and HOT + cold showers, sinks and flush toilets and an air conditioned mess hall plus an officer's club and real cement sidewalks. It was like being back in the world again."

~18 May 68 - "We were supposed to have had another monsoon season but it never started. When it does rain the flying gets tough. We still fly if the mission is important enough. ...In my last letter I told you we went to Da nang for a mission. We tried to put a special forces team into an area around a special forces camp that was overrun the camp was called Khan Duc but we couldn't get them in because there was no place we could land. Nothing but high trees and thick jungle."

~31 May 68 - "Today I flew down to Phu Bai to pick up a new ship. It was the first time that I have flown without another pilot but it was a real easy run."

There is an online picassa photo gallery site with photos from different 7th Cav units posting pictures. One slide was marked "log bird bringing in hots and sugar notes". These must of been fun missions bringing in hot food and mail from home to the ground troops!

~2 June 68 - "Today I flew for eight hours which isn't too bad. My longest day has been 13 hours which was just a few days ago, We flew mostly resupply missions that day."

~4 June 68 - "I've been flying a lot of hours each day so there isn't much time to do anything. I've flown at least 40 hours in the last four days."

~13 June 68 - "Yesterday and today I had off and didn't fly. I can't remember the last time I had two days off in a row, except for when we had the fire and the ships burnt."

~19 June 68 - "I'm still flying a lot. For the month of June I have almost 100 hrs. and today is only the 19th."

In a letter to Fred Bianchini dated 20 June 68, Ralph tells of an intelligence gathering operation when they took up in the helicopter an NVA soldier who had surrendered.

"We set up speakers all over the ship and went out in the mountains and broadcasted to the NVA to give up. Half way through the broadcasting (he) got sick and we had to bring him back so on the way back I went low level and got him real sick. haha."

~27 June 68 - "I've been grounded for a few days since yesterday because I have flown too many hours this month (144.5 hours). After 140 hrs. a month they have to give you a rest of a few days. I'm glad I got the rest because I was starting to get tired. Not many others have flown that many hours in one month. I heard today that Khe Sanh is going to be abandoned. Its about time because they don't need it any more. It doesn't serve any useful purpose anymore so they are going to drop it."

~29 June 68 - "Well today is the fourth day that I've had off. I really didn't expect that many but its good to get it. Tomorrow I will be up flying again. ...Well I'm just about an Aircraft Commander now. The whole month of June I've been flying as one. As of now I have about 280 hours which is a bit above average for the time I've been here. ..That helmet I have in the picture is mine, #18 is my call sign only when we use it you say one, eight not eighteen."

When Ralph first got to C Company it had the call designation of "ghostrider". Ralph's call sign was "ghostrider one eight". Don Sayrizi (pictured below) designed the "ghostrider" patch when he first got to C227AHB. Sometime in June or so the call designation changed to "water buffalo" then shortened to "buffalo". So Ralph's call sign was then "buffalo one eight".

Image of "Ghostrider" patch and WO Don Sayrizi

Images courtesy of Don Sayrizi/C227AHB

~2 July 68 - "Not too much has changed in the past few days. It seems like I have gone from one extreme to the other as far as flying is concerned. I have only flown one day in the past seven days and I not supposed to fly tomorrow either. Well I can use the rest anyway. It gets kind of boring just doing nothing."

~5 July 68 - "Well its about time the marines left Khe Sanh it hasn't been much good anymore. At one time it was a good block for the NVA supply route but now the NVA have found ways of going around it. The marines are just moving to the east about 6 miles to a place called LZ STUD which is just as good a place as Khe Sanh was. We didn't help them move from Khe Sanh unless one of the other of the Cav's units helped them."

~16 July 68 - "Its been getting very windy lately and that makes it tough to fly."

For more insight on what it was like for Ralph to fly missions with the 227th Assault Helicopter Battalion, I highly recommend:

An Assault Helicopter Unit in Vietnam, 1969-1970

Volume 1

Book by Matt Jackson

I have always wondered what it was like for Ralph to go through basic training, warrant officer school and flight school; and of course fly huey’s in Vietnam. Now I know!

Thanks to Matt Jackson for writing this book. As a Gold Star Sister it provided me with this invaluable treasured insight. Additional thanks to Howard Burbank (A227) for his thoughtfulness in sending me Undaunted Valor-An Assault Helicopter Unit in Vietnam with an enclosed note that reads, “Greetings Nancy, One of our former members of A/227 has just published a book about his tour with our unit. Although it covers a later time period than your brother’s tour - and is located in another part of Vietnam - the book does give an accurate and detailed account of the life of the crews who flew with the 227th Assault Helicopter Battalion during Vietnam.”

21 July 1968

PFC Bob Weiss remembers it being a beautiful day and reading the Sunday paper. His unit was told in the morning “to be ready to move on short notice”. And when they got to the LZ (Landing Zone) it would be hot. Meaning the enemy would be waiting for them. Routinely they were told LZ’s would be hot but Bob remembers thinking this time it would be for real and feels the rest of the squad knew this too. Bob was a member of a machine gun squad in the 3rd Platoon, C Company, 5th Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile). He also remembers waiting around that day for what seemed to be a long time with many delays. Tension grew with each delay. In his letter years later to Stevey Callahan (sister of Larry Callahan), Bob writes, "I don’t remember the exact time in any event we did finally lift off, once in the choppers you knew that you had to suck it up or you wouldn’t be any good to yourself or the rest of the men."

Glenn Hess a fellow C227AHB pilot and tent mate of Ralph's adds more details to the days events. "The reason for the operation on this day was based on knowledge that the NVA was massing NW of Camp Evans. The thought was that either the NVA would attack Camp Evans or LZ Nancy which had shut down essential river traffic just to the north of Camp Evans. This was a major water route for sampans full of rice that they (Viet Cong) tried to move into the mountains for the NVA. Our Night Hunter missions were to interdict or interrupt those shipments. I flew that mission every night for a week or two. The first Huey flew low level with spotlights and extra gunners looking for sampans and a C model gunship followed with its lights out. Naturally, the first Huey would take fire, they'd flip off their lights and climb while the gunship engaged. LZ Nancy was a stopper on the river traffic and that is why I think the NVA were going to attack Nancy. (Evans would have been too strong for an assault). The insertion of troops this day was on an LZ that was just south of the river that also ran past LZ Nancy. The initial lift of troops into the LZ was in the morning. We were surprised to land in the middle of an NVA regimental headquarters. That is why the fight never broke off. They usually ran but this time we were in their backyard.” By lunchtime Glenn remembers the assault was at full throttle. ... "hot loading of gunships (never turning off engines), nonstop artillery, Spooky and continuous relay of Naval air coming in off a carrier. Bob Weiss was part of the reaction force with the first resupply on their backs."

Bob Weiss remembers, "My platoon had point that day, so we were in the first group of choppers to go in, as we approached the landing zone there was a lot of debris on the ground, making it difficult to jump out and land on secure footing. I didn’t jump until the chopper moved over to a better spot. I had about 100 pounds of equipment on my back and thought I would surely break a leg. I finally jumped. ...we were receiving small weapons fire from the north east of the perimeter. We had our point squad and one machine gun facing that area, my machine gun was facing north west. The choppers were receiving fire as they came from the south moving north to land, we lost our first man who was shot as he was about to exit the chopper. Everyone else would land ok, we would lose the other ground troops before the day was over, your brother may have been flying one of the choppers that flew us in but I don’t know this for sure."

Joseph D. Deleo

I came across the following citation online while researching another story. I confirmed it with Bob Weiss. Bob said all of C Company, 5/7 (close to 100 troops) were involved with this mission. He was not aware of the bravery of the medic that day until now. But he said they never really talked about it back then. The citation tells a story as to the type of battle that was fought that day.

SPECIALIST FOURTH CLASS

JOSEPH D. DELEO

ARMY

For service as set forth in the following:

CITATION:

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918 (amended by act of July 25, 1963), takes pleasure in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross to Specialist Fourth Class Joseph D. Deleo (ASN: US-53812152), United States Army, for extraordinary heroism in connection with military operations involving conflict with an armed hostile force in the Republic of Vietnam, while serving with Company C, 5th Battalion, 7th Cavalry, 3d Brigade, 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile). Specialist Four Deleo distinguished himself by exceptionally valorous actions on 21 July 1968 while serving as a medic on a reconnaissance patrol near Hue. His platoon came under intense hostile fire from a well entrenched enemy force. One man was seriously wounded and lay in the open only twenty meters to the front of a hostile automatic weapons emplacement. attempts to rescue the man by other members of the unit were unsuccessful. With complete disregard for his safety, Specialist Deleo advanced twenty-five meters through a hail of enemy fire to his injured comrade and administered first aid. A rocket then exploded to his rear, seriously wounding another man. Specialist Deleo unhesitantly moved through the continuing fusillade to the second casualty, treated his wounds and supervised his evacuation. Almost immediately another cry for a medic came, this time to assist a soldier who had tried to extract the first casualty and was wounded only a few feet from him. As Specialist Deleo neared the position occupied by the two men, the enemy suddenly unleashed a particularly savage barrage on their location. He sprang forward, pulled the two soldiers close together and covered them with his body. He was hit in both legs and in the hand by the murderous fire, completely immobilizing him. Later, member of his element overran the aggressors and evacuated all three wounded men. Specialist Four Deleo's extraordinary heroism and devotion to duty were in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service and reflect great credit upon himself, his unit, and the United States Army.

Distinguished Service Cross - Second Highest Award

It was evening now when a desperate call came in from C Company, 5th Battalion, 7th Cavalry. A tactical emergency (TAC-E) was radioed in for additional ammunition and water to be sling loaded into the LZ. MAJ Jon Mabrey in a later article stated, "Bringing in a cargo net of ammunition meant the helicopter would be forced to lower the net in the hot LZ from a stationary position above the firefight. It was the kind of situation we all dreaded."

C Company, 227th Assault Helicopter Battalion responded to the call by asking for volunteers knowing the extreme danger. Three helicopter teams were assembled. Each helicopter had a crew of two pilots, one crew chief and one gunner on board. Yellow One was LT Delbert Bish (pilot), WO Don Sayrizi (pilot), one crew chief and one gunner. Yellow Two was WO Larry Callahan (pilot), WO Ralph Willard (pilot), SGT Robert Parent (crew chief), and SSG Robert Stone (gunner). Coincident or not all four on Yellow Two were from New England. SSG Stone pulled the initial gunner off because the initial gunner was going home in a few days. (I have since learned that both Stone and Parent tricked the inital crew chief and gunner off because they were both short. Read Chopper Warriors, Chapter 13 They Neve Came Back (below). Yellow Three was WO Glenn Hess, WO Terry Pestel, one crew chief and one gunner. Two D Company 227 Assault Helicopter Battalion "Gunships" were also scrambled to provide suppressive fire for the "hueys".

(All six C227AHB pilots were tent mates and close friends).

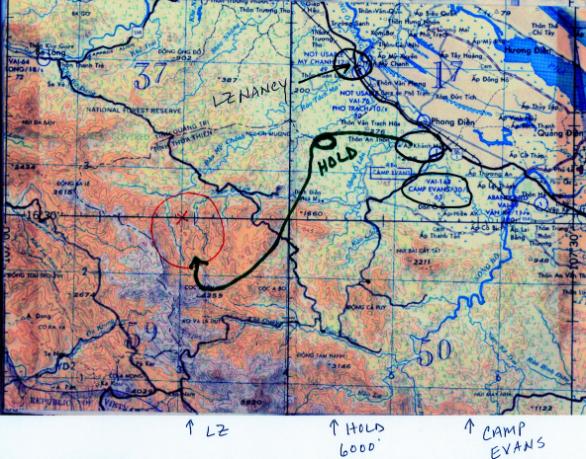

Glenn recalls, "We did not need a map that night. We could not have read it anyway. We could see where it (LZ) was from Evans. We watched the air sorties going in and we saw the artillery tube sending the rounds out there. Just as we finished dinner, we stood on our bunker and watched Spooky pouring mini gun rounds into the area. We could see the stream of tracers like the stitching on a shirt. It was close. We could not see the LZ because it as behind the first ridge line, but there was no doubt where it was. We picked up our loads on the NNW side of Evans. We flew NNW at a lower level to get out under the artillery, a 155 mm battery was on the north perimeter so we flew under their shots. We were directed to then climb to 6000 feet and hold at a point east of the ridge lines. To approach the LZ we flew SW to a point SW of the LZ. We then turned NE and flew along a ridge line in a northerly (NW) course. It was pitch black except for the flares and they were away from the LZ casting shadows. (Flares provided light for the Starlight scopes without illuminating US positions."

Prior to entering the LZ Yellow One was called off which put Yellow Two first up. Terry Pestel told me that standard procedure at night was to go in with your lights out so not to give yourself away. Yellow Two did this. Just prior to entering the LZ (within 40 to 60 seconds of Yellow Two) Yellow Three was told to put their lights on (not knowing yet of Yellow Two going down). Yellow Three while hovering with their sling load above the LZ took a hit to the bottom of the helicopter that lifted them about a foot in the air. Through radio contact with the the ground unit they learned that they were hit by a dud Rocket Propelled Grenade which hit the helicopter and then fell into the LZ. Fighting was so close that the RPG could not reach the distance needed for full impact. Yellow Three additionally took at least 21 bullet hits while hovering and waiting for the sling load to reach the ground and release! Yellow One the last to go in miraculously took no hits!

Bob Weiss writes, "I don't remember how long the fire fight had gone but we eventually had a chopper resupply us with ammunition, this was your brothers, he got in ok, dropped the ammo but when they lifted off I could hear them going up and they were moving northwest over my position when I heard an odd noise from the chopper. When I looked up the tail was rotating around making a 360 degree circle. I remember thinking that they were just having a problem controlling the chopper because there was no smoke or flames, but then the tail rotor was turning erratically and rolled over and the helicopter was losing altitude. It was obvious that they were going down. They went down about 150 meters in front of me. The call went out for volunteers to go on a rescue mission. Without hesitation I joined in. I think there was four or five of us. Time was essential because darkness was setting in. The terrain was was rough, the vegetation was very dense and it was downhill. We started down, the point man wielding a machete to clear a path. As we approached the chopper there had been no explosions and there was no fire or smoke. I do remember the sound of a hot engine as it was cooling. The chopper was pretty much intact, laying on its left side, which meant the door gunner on that side was trapped. We tried but no way could we move it. While I checked the door gunner on the right side one of the other men checked the pilots. The door gunner was wheezing loudly, sounding like a punctured lung probably from his machine gun hitting him in the chest. The pilots died apparently from the concussion with the ground. All our efforts surrounded the door gunner. It was difficult to maneuver him out of the chopper and the steep climb up the hill was looking impossible. We had brought a radio and asked for a poncho to use as a litter. We got the impression no one wanted to come down but eventually someone did come down but unfortunately before we could get back up the hill the door gunner had died. At this point it was too dark to recover the others. This was done the next morning.

In an email conversation with Bob Weiss in March 2012 he wrote, "When the Huey was shot down that day those of us who volunteered knew that those guys had come there to help us and we were willing to do the right thing for them. I was so confidant that we were going after survivors and it was truly disheartening to not be able to bring them back.

As the fighting subsided and night fell upon us we had concerns of being probed by the NVA but they never came and as the sun rose we prepared to advance into the area from which we had drawn fire. We were expecting snipers, booby traps and heavy gun fire but to our surprise the NVA had abandoned the area and we assumed that the previous days contact was meant to hold us back while they were evacuating. We only found peace and silence in an area that appeared to be a Training/R&R facility for hundreds or maybe even thousands of troops. It was so large an area and it was so well organized it had such an eerie feeling to it, you knew this was constructed by more than a group of Viet Cong."

C Company, 5/7 Daily Logs 21 July -26 July 1968

|

5-7 Cav Logs July 68.pdf Size : 14067.357 Kb Type : pdf |

New Crash Site

21 July 1968C227 Daily Log

S3 Daily Logs Courtesy of 227ahb.org

Written by William E. Peterson

Chapter 13

They Never Came Back

Written by Allan Ney

As a Huey crew chief with C/ 227th Assault Helicopter Battalion, lst Air Cav from August 1967-68, I have many stories, but the following haunts me even today after all these years.

This story speaks of two of the bravest, unsung heroes of the Viet Nam War. In July of 1968, Eddie Hoklotubbe, a native American Indian from Oklahoma was my assigned door gunner. We were on call on this particular night for any mission that might pop up: flare mission, river sampan patrol, emergency re-supply, or medevac. About 2200 hours, we’re called into Flight Operations, along with our two pilots. We’re told that an infantry unit is under attack and in desperate need of an ammunition re-supply. This is a tactical emergency.

I only have about two weeks left in Viet Nam. In fact, I’ll be released from the Army when I return to the States. Eddie is also very short, after he had previously extended his tour for an additional six months to be a door gunner.

Eddie and I immediately go out to the flight line to place the machine guns and ammo on the aircraft. While we’re prepping the ship, our pilots come out, put their gear in the ship, and are about ready to go. Suddenly our Platoon Sergeant, Robert Stone, and crew chief, SP/5 Bob Parent, show up on the flight line and tell my gunner and I to report back to flight operations. The mission has changed.

We head back to the Ops tent to see what’s changed and hear our Huey crank up when we’re almost at Operations. We watch in amazement, while our chopper lifts off into the very dark night. When we walk into the Operations tent, the Aircraft Commander is relaying a message on the radio for us from Sgt. Stone and Bob Parent. The message is,

“Ney and Eddie are way too short for this mission. We’ll see you in the morning.”

This crew did not come back from that mission. Whenever a dangerous mission takes place, the crews that aren’t flying hang around the Operations tent listening to the radio transmissions to see how their buddies are doing. When these heroes flew into the extremely hot LZ that was under attack, they quickly dumped their load of ammo with the help of several grunts “on the ground and took off into a hail of enemy fire. They were shot down and the entire crew was killed.

This was not their mission, but because Eddie and I only had days left in the country, our buddies did not want us to risk our lives. In turn they made the ultimate sacrifice and gave their lives in order to save ours. This happened on a regular basis in this war – soldiers sacrificing their lives, so that their brothers might live.

I knew both men well, but was especially close to Sergeant Stone. For years I have felt extreme guilt over the loss of my buddies. After years of searching, I finally found Sergeant Stone’s family. When I visited them, we had a very sad, though good discussion. The family and I are now great friends.

Note from Bill Peterson:

"Bob Parent slept in the cot next to me in the crew chief tent. He was always a very jovial guy and we became great buddies. I remember that he chewed mouthfuls of Beechnut tobacco. Whenever he spit, I asked him why he always had to spit it out? I told him if it was that bad, he should quit chewing."

—Bill Peterson

Added to website with permission from both Bill Peterson and Allan Ney

Chopper Warriors can also be purchased from iBooks

Yellow Two

Willard, Callahan, Stone, Parent

View of LZ 374225 from Camp Evans

Photo Courtesy of Bob Witt/a227ahb

View of LZ374225 Area Fifty Years Later

Photo and Satellite Images Courtesy of Julie Kink

Julie Kink, fellow Gold Star Sister (WO David Kink) and dear friend, emailed me this photo from her visit to Vietnam in October of 2018. She was on a trip back to Vietnam with her husband, Mike Sprayberry (LtCol, US Army Retired, CMOH). Others in the group included another dear friend, Chuck Kinnie, (B1/9 LOH Pilot 1968). They were there to visit an excavation site in another location and gain more information on their lifelong quest to recover the bodies of fallen American soldiers.

The following is an explanation of the photo Julie initially sent and the three screenshots that followed:

1) a screen shot of the photo showing the GPS data from my iPhone including a map of the location where I took the photo. In answer to your question, our driver had stopped the van and our group had gotten out to walk around a little and Mike mentioned to me that looking that direction was toward the area where Ralph and Larry were flying, so I took the photo. Despite five trips, I don't know my way around Vietnam like Mike does. I don't know how close or far we were. I also wish there weren't power lines in the photo, but you know how that goes!

2) a screen shot of a satellite image where the photo was taken, using my fledgling legal land converter skills (latitude/longitude to grid coordinates) that Mike has been teaching me. This shows that I took the photo on Highway 1.

3) a screen shot of a satellite image showing the crash location according to the grid coordinates provided by Bob Weiss in the VHPA incident report (NOT the incorrect grid coordinates noted at the top of the incident report). This shows how far the site was from where the photo was taken, also how very heavily forested and mountainous the area is.

The Young Men Killed In Action on 21 July 1968 supporting this Mission

C Company, 5th Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment

1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile)

C Company, 227th Assault Helicopter Battalion, 11 Aviation Group

1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile)

Warrant Officer One Ralph John Willard